A sporting biopic unlike any other, Martin Scorsese’s astonishing masterpiece Raging Bull (1980) is surely one of the greatest cinematic achievements of all time. Although many rightly claim it to be the greatest sports movie of all time, Raging Bull’s praise should not merely be confined to one genre, as it is unquestionably one of the finest pieces ever committed to film.

Charting the incredible rise and fall of middleweight boxer Jake La Motta Raging Bull remains absolutely unflinching in its depiction of this complex, brutal and ultimately unique individual. From his early years as a young boxer of enormous potential, through his destructive and erratic relationships with his wife and brother/manager, and eventually his latter years as a seedy club owner and stand up comedian, Scorsese provides a painfully honest, yet remarkably beautiful depiction of each and every aspect of La Motta’s professional and personal life.

Charting the incredible rise and fall of middleweight boxer Jake La Motta Raging Bull remains absolutely unflinching in its depiction of this complex, brutal and ultimately unique individual. From his early years as a young boxer of enormous potential, through his destructive and erratic relationships with his wife and brother/manager, and eventually his latter years as a seedy club owner and stand up comedian, Scorsese provides a painfully honest, yet remarkably beautiful depiction of each and every aspect of La Motta’s professional and personal life.While it may seem as though heaping superlatives upon a film already assured of such magnitude and critical acclaim as Raging Bull is hardly an original approach to its scrutiny, I find it virtually impossible to find even a single fault in this most perfect of films. Rarely does one encounter a movie in which each of its components are so expertly woven together to create such a perfectly cohesive whole.

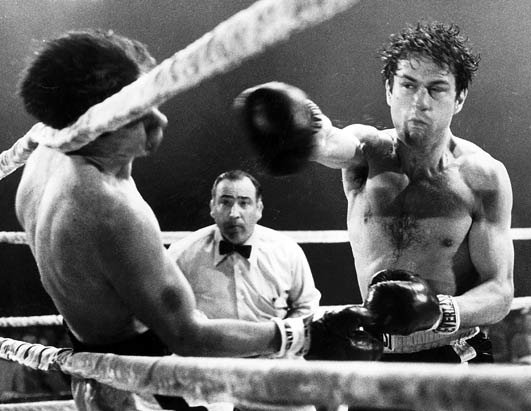

Arguably the most obvious of these components is Robert De Niro’s performance of La Motta, as he takes his famous methodical approach to unrivalled extremes. Aside from the well documented commitment De Niro provided with regards to the film’s fight scenes - sparring and training with La so extensively as to supposedly render him good enough to turn pro – the level of intensity brought to the character must rank alongside, in my view, his all time greatest performance as Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976). His portrayal of La Motta’s decline and psychological disintegration can often be painful to watch; the scene in which we see him in a jail cell weeping whilst punching and slamming his head into a brick wall being one of the film’s most violently powerful moments.

However, it is not just De Niro that is on fine form; similarly brilliant in his performances is Joe Pesci as Joey, La Motta’s brother and manager. The loving, yet intensely strained relationship between the two is genuinely moving. For an example of just how good these two are on screen together, one need look no further than the famous confrontation scene in which Jake accuses Joey of having an affair with his wife. With each and every second that passes, the tension becomes more and more unbearable; rivalling the more physically intense fight scenes in terms of sheer emotional conflict.

Equal to the supreme performances on offer is Scorsese’s breathtaking direction. From the opening slow-mo sequence of La Motta pacing and bouncing around a smoke filled boxing ring, the sense of impending danger is raised immediately to dizzying heights. Scorsese runs with this tone and then amplifies it with each of the film’s explosive fight scenes. The heightened sense of savage realism in these moments make for a viewing experience unrivalled by any other boxing movie; placing the camera and the audience inside the ring rather than outside, creating a tone of claustrophobia and offering no escape from the action taking place.

As proven with their subsequent works together - Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995) - when the formidable talents of Scorsese, De Niro and Pesci combine, the results are never short of impeccable. Yet, for me, Raging Bull’s ground-breaking and distinctive approach to an often formulaic genre results in this trio’s greatest success. A genuine work of genius.